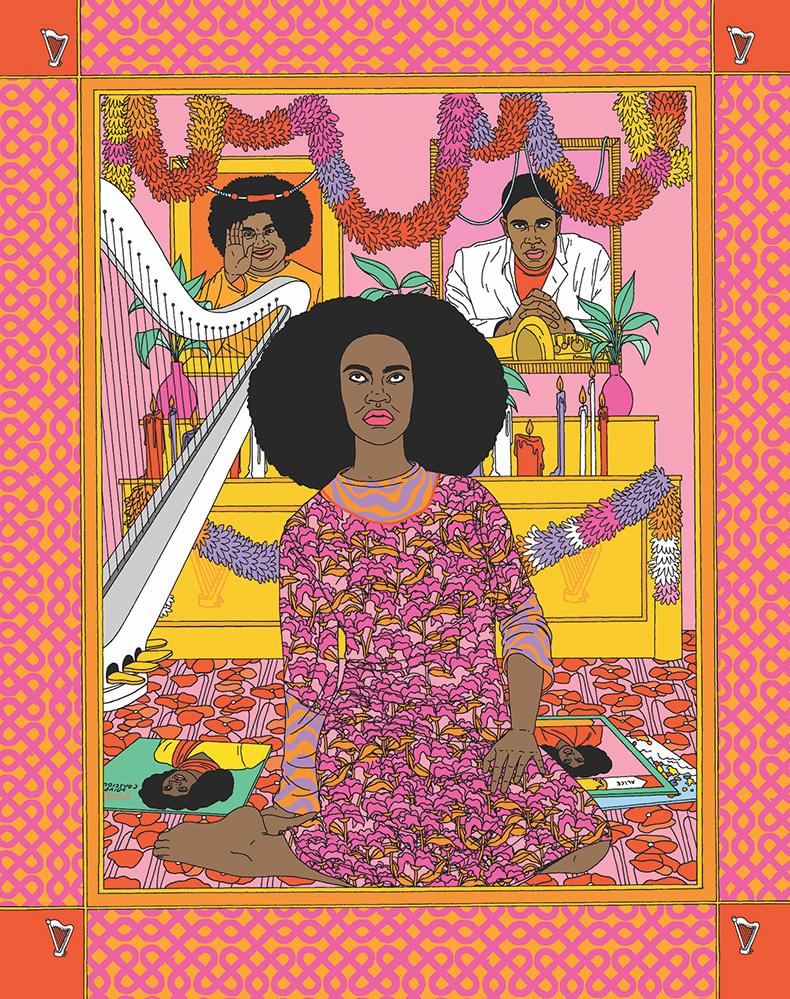

A respected yet divisive figure who was scorned by the jazz mainstream for most of her life, Alice Coltrane was one of the most complicated and misunderstood of all 20th-century musicians. In this century‚ however‚ her music has grown in stature‚ and one can now hear echoes of her influence everywhere‚ from Björk’s juxtaposition of timbres and textures to Joanna Newsom’s harp playing to the twisted astral beats of her great-nephew Stephen Ellison, aka Flying Lotus. While her late husband John Coltrane’s discography remains titanic in modern jazz, Alice’s own albums are equally compelling and mysterious, suggesting a musical form that moves away from jazz and into a unique sonic realm that draws on classical Indian instrumentation, atonal modern orchestration, and homemade religious synth music. The adventurous nature and spiritual import of her work continues to resonate through New Age, jazz, and experimental electronic music of all stripes.

Alice used a number of names throughout her career, and collectively they chart a path of self-realization. The names she adopted demarcate radical shifts in her life and her work, serving effectively as chapter headings in the story of how a bebop pianist from Detroit evolved into one of jazz’s singular visionaries, ultimately walking away from public performance to become a guru and beacon of enlightenment for others.

Alice McLeod was born on August 27, 1937, in Alabama, though her family soon relocated to the rough east side of Detroit. The two World Wars solidified Detroit’s position as a manufacturing powerhouse and by 1959 it was the industrial center of the country. It had also gained renown as a bebop hot spot and was home to future jazz players like Cecil McBee, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, Milt Jackson, Yusef Lateef, Bennie Maupin, and Elvin Jones.

The McLeods were a musical family—Alice’s mother, Anna, played in the church choir, her half brother Ernest Farrow was a prominent jazz bassist, and her sister Marilyn went on to be a songwriter at Motown—and Alice took up piano and organ at a young age. As a teen she accompanied Mt. Olive Baptist Church’s three choirs, and at 16 she was invited to perform with the Lemon Gospel Singers during services at the more ecstatic Church of God in Christ. In Franya J. Berkman’s biography Monument Eternal: The Music of Alice Coltrane, Alice remembers those formative services as “the gospel experience of her life,” an instance of devotional music that gave her teenage self “the experience of unmediated worship at the collective level.”

Encouraged by her half brother Farrow, Alice continued to pursue music. She formed her own lounge act, performing gospel and R&B—with touches of blues and bebop—around Detroit. The young McLeod soon became a fixture of the city’s jazz scene and found herself involved with Kenneth “Poncho” Hagood, a scat jazz singer who’d recorded with Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis. The young couple were wed and relocated to Paris in the late ’50s.

Alice gigged regularly around Paris, befriending other musicians like fellow pianist Bud Powell. In 1960, she gave birth to a daughter, Michelle—the joyousness of which was tempered by Hagood’s burgeoning heroin habit. It wasn’t long before she returned to Detroit as a single mother, moved back in with her parents, and started picking up gigs to support her daughter. Once again immersed in the bustling Detroit scene, McLeod began to contemplate jazz beyond the dizzying array of chord changes, scales, and standards that were fundamental to the bop era. One album in particular spurred her creative contemplation: John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass.

While known to be a junkie early in his career, by 1957 tenor saxophonist John Coltrane had kicked his habit and begun his musical ascent in earnest. He was a sideman for Thelonious Monk and in 1959 appeared on Miles Davis’ modal masterwork, Kind of Blue. Coltrane was already an accomplished bandleader, releasing a slew of records from Blue Train (1957) to My Favorite Things (1961). Firmly established as one of the greatest tenor saxophone players of his generation, he signed an exclusive recording contract with Impulse Records—the brand-new jazz imprint of producer Creed Taylor.

Coltrane’s new deal allowed him the creative control and artistic freedom necessary to push jazz’s boundaries and imagine new musical vistas. Africa/Brass was his first album for Impulse and featured a 21-piece ensemble that included the preeminent reedman Eric Dolphy backed up by the rhythm section of pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones. Cuts like “Africa”—an expansive suite augmented by birdcalls and jungle sounds—announce Coltrane as a tireless innovator, using Davis’ modal template as the launching pad for new explorations.

Alice went to see John and his new quartet when they played Detroit’s Minor Key club in January of 1962. She didn’t speak to him that night, but an opportunity to play piano in vibraphonist Terry Gibbs’ ensemble brought her to New York City in the summer of 1963, where Gibbs’ group opened for John’s quartet during an extended engagement at Birdland. When her group wasn’t on the bandstand, Alice tried to work up the nerve to talk to the saxophonist.

She describes her initial impressions in Berkman’s book: “I had an inner feeling about him. ... I was connecting with another message that I had perceived as coming through the music. At Birdland, that same feeling would come back, something that I comprehend was associated with my soul or spirit.” The two musicians barely spoke, though Alice described John’s silence as “loud.” A few days later, still having exchanged very few words, Alice heard him playing a melody behind her. She turned and complimented him on its beautiful theme. He said it was for her.

John and Alice’s relationship began in July of 1963 and they were married in Juarez, Mexico, in 1965. They remained together until his death from liver cancer two years later. Alice gave birth to their three sons: John Jr., Ravi, and Oran. While the couple only began to record together in February 1966, their musical relationship spanned the duration of their romantic relationship, both predicated on mutual inspiration and spiritual elevation.

Alice had felt limited by the rigidity and orthodoxy of bebop throughout her career and, as her relationship with John bloomed, she found his influence on her musical explorations to be profound. The couple used musical innovation as a path toward personal enlightenment: “You heard all kinds of things that would have just been left alone, never a part of your discovery or appreciation,” she said. It’s difficult to gauge the degree to which her approach to the piano changed once she met John, as aside from a few Terry Gibbs albums released in 1963 and 1964, few if any recordings of Alice’s early performances exist.

John Coltrane’s discography from 1963 until 1967 demonstrates a restless urgency to expand every aspect of his horn and his music. Two Impulse albums from 1963 find him exploring ballads and collaborating with Duke Ellington and vocalist Johnny Hartman. While some critics see these albums as a response to being labeled “anti-jazz” by DownBeat in the early ’60s, in hindsight they seem to serve as a reset and resting place—a last look back toward jazz history before John and his group forged ahead into an exploration of innovative new sounds.

At the end of 1964, Coltrane entered engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio in New Jersey with his classic quartet—pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and thunderstorm drummer Elvin Jones—to record a four-part suite documenting a spiritual conversion. “This album is a humble offering to Him,” Coltrane wrote in the liner notes to A Love Supreme. “An attempt to say ‘THANK YOU GOD’ through our work.” It’s the summation of the quartet’s lyrical, evocative, and dynamic power.

Within that same year the quartet would both expand, with the addition of second saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and second drummer Rashied Ali, and fray, with Tyner and Jones leaving. “All I could hear was a lot of noise,” Tyner said in one interview. “I didn’t have any feeling for the music.” Starting in 1965, Coltrane embraced fiery free jazz, a sound that sought freedom from meter, chord changes, harmonies, and whatever else had previously defined and codified jazz. The influence of younger horn players like Sanders, Archie Shepp, and Albert Ayler on John is well documented, but very little has been said of the musician who replaced Tyner on the piano bench: Alice Coltrane.

Biographies of John Coltrane often reduce his marriage to a relationship between mentor and disciple, with John as the musical guru and Alice as the initiate. “Many of John Coltrane’s fans viewed her as accomplice to the so-called anti-jazz experiments of his final years,” Berkman writes, a sentiment that stemmed from “the controversial role she assumed when she replaced McCoy Tyner as pianist in her husband’s final rhythm section.” (Years later, Alice Coltrane contributed harp to Tyner’s 1972 album Extensions.) Four years before Yoko Ono allegedly broke up the Beatles, thereby earning the scorn of all future generations of rock fans, Alice was accused of breaking up the greatest jazz group of the mid-’60s.

But Alice, if anything, was the catalyst for Coltrane’s greatest music, abetting and inspiring his spiritual quest to realize a universal sound. When the couple met in 1963, Coltrane was still working within the framework of modal jazz. Soon after Alice entered his life, he started to push beyond the conventions of modern jazz, freeing himself from meter and steady tempo, fixed chord changes and melody. A Love Supreme was composed and realized after their relationship began. Seen in that light, the questing Coltrane albums Ascension, Om, Meditations, and more all stem from this relationship. Without Alice’s own roots in the ecstatic spirit of the Church of God in Christ services and a shared interest in a less dogmatic and more universal understanding of God—to say nothing of their love and devotion to each other—would Coltrane’s own spiritual transformation have occurred?

The Coltranes’ spiritual study did not take place in a vacuum, but amid a broader religious upheaval and restructuring of the ’60s. New forms of Afrocentric spirituality ranged from a renewed interest in Egyptology and the rituals of Santeria to Ron Karenga’s creation of Kwanzaa and the rise of the Nation of Islam. But Alice herself acknowledged that the new couple’s pursuit intensified soon after they came together. “What we did was really begin to reach out and look toward higher experiences in spiritual life and higher knowledge,” she told Berkman. Despite Alice’s history in the church and her subsequent life as a swamini, she still receives little acknowledgment in biographies and jazz history as catalyst for her husband’s spiritual rebirth.

Alice herself didn’t do much to correct these accounts. As the decade rolled along and music—as well as societal roles—became increasingly radicalized and questioned, Coltrane embraced her role as wife and mother. In a 1988 radio interview, she said of her marriage, “I didn’t want to be equal to him. I didn’t have to be equal to him and do what he did. That, I never considered. I don’t think like that. And whatever in the women’s liberation—that’s what they want. I didn’t want to be equal to him. I wanted to be a wife. ... To me, as a result of that association, it fully manifested. There was no more question about direction.”

Once Alice joined her husband on the bandstand, they toured the world, the music going further and further out, with standards like “My Favorite Things” pushing toward the hour mark. Not that critics always noted her. In a February 23, 1967, DownBeat review of Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, Alice warrants but a single line in a 15-paragraph review: “Mrs. Coltrane’s piano support is always firm and appropriate, never overbusy or obtrusive.”

And then, in May of 1967, John Coltrane complained of abdominal pain that was soon revealed to be liver cancer. By summer, he could no longer eat, and he left his earthly body on July 17, 1967.

In quick succession, Alice suffered the loss of both her husband and her half brother Ernest. Her account of her spiritual awakening between 1968 and 1970 in her self-published tract, Monument Eternal, is harrowing: her weight plunged from 118 to 95 pounds, and her family worried for her well-being. In her telling, her weight loss was not the result of grief and depression but due to extreme austerities undertaken for spiritual advancement. It leads to detached remembrances, like: “During an excruciating test to withstand heat, my right hand succumbed to a third-degree burn. After watching the flesh fall away and the nails turn black, it was all I could do to wrap the remaining flesh in a linen cloth.”

The rainbow-covered booklet makes no mention of her jazz music career, her husband, or her travels to India. Instead, she matter-of-factly details making a doctor recoil in horror at the sight of her blackened flesh, what occurs when one experiences supreme consciousness, the nuances of various astral planes, her ability to hear trees sing, and scaring the family dog with her astral projections. Amid this, her family feared for her sanity: “My relatives became extremely worried about my mental and physical health. Therefore they arranged for my return to their home for ‘care and rest.’” Later she adds: “Communicating with people was found to be like suffering judgment. In fact, it was almost impossible for me to dwell upon earthly matters, and equally impossible for me to bring the mind down to mundane thoughts and general conversations.”

Deep in this quest, Alice assumed control of her husband’s formidable estate and released his first posthumous album in September 1967, Expression. And while DownBeat gave it four stars, Don DeMichael wrote: “Mrs. Coltrane, while sounding somewhat like McCoy Tyner, does not have her predecessor’s physical or musical strength.” She released her first album as leader, A Monastic Trio, the following year. On it, she referred to her husband by her spiritual name for him, Ohnedaruth (“compassion”), and sought to follow his example to create a music that was free, open-ended, and spiritually questing. The album features late-period quartet bandmates Pharoah Sanders, Jimmy Garrison, and Rashied Ali, with Alice on piano as well as a new instrument for her, harp.

Alice’s self-taught playing style on harp—ordered for her by her husband, who didn’t live to see its arrival— was full of glissandi and accentuated arpeggios and took cues from another Detroiter, Dorothy Ashby, but Coltrane’s playing was decidedly more abstract. She compared the piano to a sunrise and the harp to a sunset, marveling at “the subtleness, the quietness, the peacefulness” of the latter instrument. It would figure prominently in her future albums. Such subtlety was lost on critics at the time, with *DownBeat’*s review of A Monastic Trio labeling Alice’s playing as “a wispy impressionist feeling without urgent substance.”

Fans and critics expecting the strength and urgency in her husband’s music were befuddled by Alice’s approach as a bandleader. DownBeat wrote of one album: “It seems incredible that a group so heavily stamped by the late John Coltrane would not be able to pull off an album, but that’s just what happens here.” As more posthumous John Coltrane albums came to market, some featuring Alice’s own harp and string arrangements on top of previously recorded sessions, critics were enraged by the perceived blasphemy.

“Black female musicians have been quintessential others, overlooked because of … gender, race and class,” Berkman writes. “Black female musicians rarely transcend difference and obtain the status of artist.” In the context of such overt racism and sexism, Alice’s early solo albums were at odds not only with jazz’s “New Thing”—chaotic free-blowing sessions that roared and shrieked for entire sides of vinyl—but also with late-’60s radicalism and black power. At a time when African American female artists from Abbey Lincoln to Nina Simone were growing more and more politically outspoken, when riots and protests were roiling the inner cities of America, Alice’s music was the diametric opposite of such trends: introspective and contemplative, gentle and impressionistic.

Cecil McBee, a jazz bassist who played with Alice at the turn of the decade, says of her position and approach: “Where we were trying to come from [as free jazz musicians], with the loudness and bombast of our music, she made these statements in a more delicate, graceful, articulate, and uniform way.” She was intentionally making something softer than protest music; she wasn’t demonstrating on the bandstand. In an era when national, racial, and gender identity were highly contentious, Alice Coltrane was aiming for transcendence.

The Coltranes’ universalist view, which dates back to A Love Supreme, came into focus for Alice Coltrane in 1969, when she was introduced to a figure who clarified her spiritual path and resolve, Swami Satchidananda. Invited to New York City by film director Conrad Rooks, Satchidananda came to visit in 1967 and began to lecture at the Unitarian Universalist Church in the Upper West Side, soon establishing the first Integral Yoga Institute on West End Avenue. Within a few years, Satchidananda made the spread in Life magazine’s “Year of the Guru” issue and then sold out Carnegie Hall. He later opened the ceremonies at Woodstock. Alice gravitated to his Eastern philosophy of self-knowledge and became close friends with the Swami.

Anticipating a trip to accompany the Swami through India, Alice Coltrane entered the studio in 1970 to record what is arguably the most sumptuous spiritual jazz album of the era, Journey in Satchidananda. The liner notes speak of that upcoming voyage, but the music itself reveals that a stunning internal shift has already occurred, fitting for the cryptic title, in that “Satchidananda” is not an external destination to be journeyed to, but rather a place to be discovered within. Augmented by oud, tamboura, Sanders’ soprano saxophone, and McBee’s bowed bass, Alice’s assured harp playing takes on a Technicolor vibrancy, entwining with Indian overtones to create a divine music that transcends not only the limitations of jazz but of both Eastern and Western music, and anticipates the rise of New Age music at its most resonant.

McBee described the sessions to Berkman as intimate: “It was very, very spiritual. The lights would be low and she had incense and there was not much conversation ... about what was to be. The spiritual, emotional, physical statement of the environment, it was just there. You felt it and you just played it.” The month after Satchidananda was released, Alice accompanied the Swami to India for a five-week trip, visiting New Delhi, Ceylon, Rishikesh, and Madras. She brought her harp with her, an exotic sight to most Indians, and also began to learn Hindu devotional hymns.

Alice returned from the pilgrimage and recorded her next album, Universal Consciousness, shortly thereafter. It deftly mixes orchestral strings, Indian timbres, harp, and the Wurlitzer organ, an instrument Alice said had been revealed to her in a vision. It was a music she described as a “Totality concept, which embraces cosmic thought as an emblem of Universal Sound.” And while a fellow devotee of Indian music, George Harrison, might have set Hindu chants to folk-rock arrangements, Alice saw in them something both avant-garde and transcendent. One won’t mistake her version of “Hare Krishna”—with a harp and orchestral arrangement that could levitate mountains—for what you hear chanted in Union Square. Even DownBeat couldn’t deny its majesty, calling Universal Consciousness a “paragon of the new music. … [Alice] emerged as the strongest of Coltrane’s disciples. Her leadership affects everyone, consequently producing a stunningly beautiful result.”

That adoration was short-lived in the press, with her last two albums for Impulse getting dismissive reviews. World Galaxy earned two and a half stars, lambasted as “super-saccharine, often corny and terribly repetitive,” while Lord of Lords was described as being “not much more than pretty music … made up of little more than strung-together arpeggios and glissandi … a massive swaying smear.”

For Alice’s great-nephew, Flying Lotus, the turbulent and beautiful Lord of Lords goes far deeper: “For me, that record is the story of John Coltrane’s ascension. It’s her understanding and coping with his death. In particular, ‘Going Home,’ that’s a family song. When someone passes, that’s the song we play at the funeral. When my auntie passed, we played that one. When my mom died, we played it for her.”

In 1976, Alice received a divine message to start an ashram and renounced the secular, beginning her new life clad in the orange robes of the Swamini. And while there were a few more studio albums for Warner Bros., for the most part, her music no longer consisted of original compositions but rather iterations of Indian hymns. Beginning on her first trip to India, Alice began to adapt bhajans—the Indian hymns associated with the Bhakti revival movement of India—to be sung at worship services at the ashram. Her last two Warners albums, Radha-Krsna Nama Sankirtana and Transcendence**, both released in 1977, comprised such devotional music, and soon after, she no longer performed in public or recorded for a label. A few years later, a series of four albums was self-released on cassette: Turiya Sings (1982), Divine Songs (1987), Infinite Chants (1990), and Glorious Chants (1995). The music within reveals a private universe of cosmic contemplation, the Swamini accompanying herself on electric organ, sometimes with her students chanting along with her. It’s a disarming music, both solemn and celebratory, haunting yet joyous.

When she removed herself from the material world to devote herself to more spiritual matters later that same decade, writing four books about her divine revelations, she was called Swamini Turiyasangitananda by her devoted students, an eight-syllable name that translates from Hindi as “the Transcendental Lord’s highest song of bliss.” Coming into prominence in an era when almost every rock star and jazz musician dabbled in Eastern mysticism and wrapped themselves in spiritual clothing only to drop them later, Alice embodied that change wholly, turning away from public acclaim and becoming a Hindu swamini and teacher.

As a child, Flying Lotus visited Alice at the ashram every Sunday: “It’s a very beautiful place, very musical. After my aunt would speak, she would play music. She’d be on the organ and people would bring instruments and there would be singing and chanting. The sounds Auntie would get out of that organ were crazy. I still never heard anyone play like that. It was super funky. As a kid, I didn’t have an appreciation for it. Now I have a different perspective on it.” Ellison told me that as a young teenager, he traveled to India with his aunt and witnessed strangers on the street drop to their knees to kiss her feet, realizing her divine presence.

To get to the Sai Anantam Ashram, one must drive through the entire length of the San Fernando Valley, toward the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Monica Mountains, before turning down a road that winds through Agourra Hills, the land brown and red with tufts of white and green brush. Past a vineyard and an equestrian center, there is a dirt road to the ashram’s gate, which is open to the public for only four hours each Sunday. The grounds are almost silent.

On a bright Sunday afternoon, there are only eight people at the Vedantic Center’s service. Plastic patio chairs line the walls of the unadorned room and marigold throw pillows are scattered throughout atop plush royal-blue carpet. The devotees, clad all in white, sit still yet sing with great fervor. Music fills the room; led by an organist situated between garlanded portraits of Sai Baba and Swamini Turiyasangitananda, the gathered sing more than a dozen hymns, accompanied by organ and the hand drums, bells, and rattles that the devotees play themselves. The bhajans segue into one another, and, curiously, these Indian hymns have a Pentecostal gospel feel to them, the blues coursing through each mesmerizing movement to suggest a place where Southeast Asia and the Deep South of America meet.

After the two-hour service is concluded, the small congregation gathers for fellowship. Since the Swamini’s passing on January 12, 2007, only seven people live at the ashram. Over carrot-raisin bread and a paper cup of strawberry lemonade from Trader Joe’s, the remaining devotees of Turiyasangitananda discuss the upcoming anniversary of their Swamini’s passing. The word death is not used. One member says that they should no longer call it a “memorial,” as that word lingers on the past. Another offers up a suggestion: The anniversary should be called an ascension, as a way to keep the blessed Swamini Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda forever in the present.

This story originally appeared in our print quarterly, The Pitchfork Review*. Buy back issues of the magazine here.*