This story originally appeared in our print quarterly, The Pitchfork Review*. Buy back issues of the magazine here.*

In the summer of 1963, a tenor saxophonist named Albert Ayler moved into a room in a flat owned by his aunt, across the street from St. Nicholas Park in Harlem. It wasn’t the 27-year-old’s first trip to New York City, but this time he’d come intending to stay. Ayler was heading into the New York jazz epicenter as a complete unknown. It was a tumultuous time for a music in the process of splintering into fragments, building on its storied past but unsure where it would go next. Giants of bebop like Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk were alive and well and cutting important records (the latter would in another year be on the cover of Time); Miles Davis was in a transitional period, but was on the verge of making some of his finest work, with his second great quintet right around the corner; Charles Mingus was humming at a creative peak, and Duke Ellington had been canonized but was still busy. If you wanted to be someone in jazz during this era, a time when the music still commanded attention, New York, then as now, was the place to be.

But for all the living history and the legends still making rent playing nightclubs and theaters around town, the real story in jazz in 1963 was the “new thing”—free jazz, introduced by Ornette Coleman in 1959 and codified in 1961 with his album bearing the name. By abandoning chords, the harmonic foundation of Western music, free jazz opened up new avenues for improvisation but also suggested the possibility of chaos. As the decade wore on, the sound and style of free jazz was closely identified with the black liberation movement, serving as both a metaphor—culture that breaks free of oppressive structure—and, through its sound, a direct expression of pain, anger, and redemption. The music developed alongside movements in other mediums. The cover of Coleman’s Free Jazz featured a detail from a painting by abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock; the splatter of paint, seemingly random but suggesting a deeper form, mirrored the approach of the musicians. It was the art of the accelerated moment, reflecting the hum and technological bent of the modern American city, and New York was its cradle. The jazz mainstream, however, was at this point still highly skeptical.

John Coltrane, who’d had a busy career as a sideman in the 1950s and had played with nearly everyone mentioned above at one time or another, was enamored with Coleman’s innovations, and was by 1963 busy shaping them to his own highly personal ends (in another 18 months he’d release A Love Supreme and would begin the fiery, intense march through music that consumed his last few years on Earth.) If the harmonically complex small-group form of bebop had transformed jazz from dance music to art music—sound designed to accompany careful listening instead of movement—free jazz forced listeners to reckon with fundamental questions about the nature of music itself. Naturally, many have no interest in this kind of introspection—they just want something that sounds good. So the life of a free jazz musician has often been a lonely and impoverished one. Albert Ayler, obsessed with the music of Coleman and Coltrane, had an idea that he could do something new with their innovations, a music as far out, and that exploded with energy, but that also had the grounded spirituality of the church.

That Ayler stayed with his aunt in New York was appropriate because family meant a great deal to him. His deeply religious parents, living in the middle-class neighborhood in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, were still very much part of his life, and he referred to himself as a mama’s boy, someone who “wore short pants” well into his teenage years. His younger brother, Donald, who shared Albert’s interest in music but hadn’t yet demonstrated the same level of skill, had always been a close companion.

Ayler had spent much of the last five years in Europe—first stationed in Orléans, France, during a three-year stint in the army, and then mostly in Copenhagen and Stockholm, where he bounced around, playing in different groups before a landing an on-and-off gig with avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor that lasted several months. He’d recorded as a leader while in Europe, but few people had heard his records. His first album, cut in Sweden in 1962 and called Something Different!!!!!!, was released on a tiny label, and Ayler was reluctant to even record it in the first place. As he described it, the music he heard in his head hadn’t quite taken shape—he was imagining something beyond what he could reproduce, and he felt he was too early in his development to document his playing. But he did feel like he was on to something, that there was a sound beyond the limits of traditional jazz that he could explore, and he saw how his music could affect people. “When I was in Sweden, the people said, ‘Beautiful!’” he told an interviewer in 1970, speaking about the first time his unorthodox style of playing had been appreciated. “I said, ‘Oh, this is beautiful?’ They said, ‘If this is what you feel, it’s beautiful.’”

Ayler made friends easily. He was charming, soft-spoken, and thoughtful, with a slightly spacey presence, prone to connecting ideas about music to broader ideas about spirituality and the cosmos. The religion he grew up with never left him; in fact, it intensified as time wore on, taking on elements of the aquarian pantheistic New Age spirituality that was emerging in the ’60s. For Ayler, music was about tapping into universal vibrations that existed at a level outside of human consciousness, and he saw his art as a way to access something higher. He never fit the mold of the cool, laconic New York jazz musician; his style was more open and more excitable. As the decade wore on, Ayler’s far-out musings would intersect with the mainstream in unusual ways, even as his music always existed well outside of it.

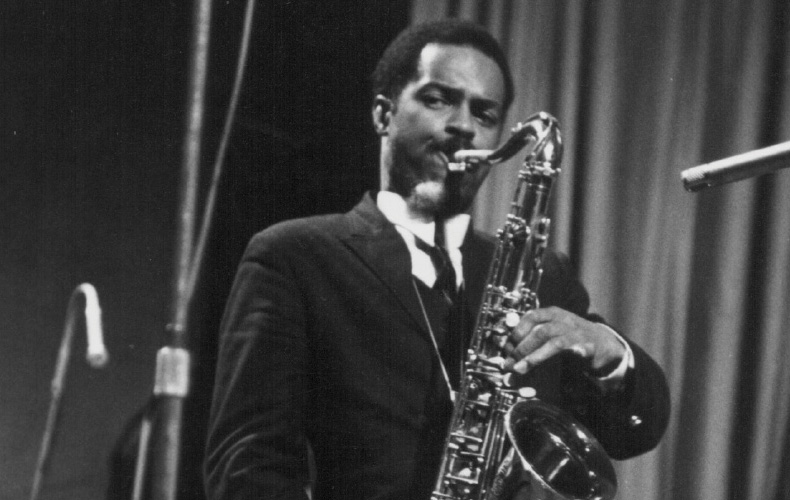

Photo by David Redferns/Redferns/GettyImages

At first, though, Ayler’s time in New York was all about the jazz scene, trying to fit in and make connections and be heard. The first semi-regular gig Ayler landed in the city was playing the Take 3 coffee house on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village, working as a sideman with Cecil Taylor, with whom he had re-connected after their European stint. The Take 3, while never notable as a jazz venue, was part of a bustling scene in the neighborhood. Three years earlier, Nat Hentoff had written a piece for The New York Times outlining how the Village had become a hotbed for adventurous jazz. In years prior, the jazz scene had been centered further uptown, first in Harlem, and later along 52nd Street. The coffee house scene in the Village, which nurtured the rise of folk music and spoken-word performance, was receptive to the new music. In 1959, Ornette Coleman’s notorious New York debut had happened a few blocks away from the Take 3, at the Five Spot, where he had extended engagements in late 1959 and early 1960. Everyone had to see Coleman and weigh in on what he was doing; it was a place to be seen and was understood to be ground zero for a radical shift in music. Some of that furor had died down by 1963, but big changes were still ahead.

The shape Ayler’s music would eventually take was some distance from the dense, complicated, often atonal music favored by Taylor. Still, Ayler left an impression on those who heard him. Robert Levin, a jazz critic who wrote frequently for the Village Voice, first heard Ayler at the Take 3 in 1963 and described the sound as “astonishing,” the sort of sound that chased some people out of the room while those who remained were riveted.

Ayler was defined by that sound—when people heard him, they could tell he was something special after just a few notes. In high school back in Cleveland, he’d spent two summers touring with a band led by Little Walter, who had changed the sound of the harmonica in Chicago-style electric blues. Practicing relentlessly since he started playing as a boy, Ayler had developed a big, rich, honking tone, the kind of sound that could cut through a noisy bar and urge people onto the dance floor. Along with the sheer volume of his attack, Ayler gradually began to favor a sometimes absurdly wavering vibrato, which evoked the pathos of gospel music and brought to mind the mournful sound of an early 20th century New Orleans funeral processional. The final piece of his saxophone sound snapped into place when he found a way to integrate his booming tone and gospel-derived emoting in the context of free jazz, with its flowing and forgiving relationship to pitch and openness to screeching and bellowing at the horn’s extreme ranges. Ayler was finding that he could integrate all of these elements into new compositions he was writing, tunes that alternated catchy, sing-song melodies inspired by European folk songs and the propulsive marches he learned in the army band with highly textured and high-energy abstract playing almost completely divorced from form. It was an unusual mix of the cerebral and highly technical and the nakedly emotional.

The New York jazz scene had developed some ambient awareness of Ayler because of his stint with Taylor at the Take 3, but his breakthrough moment would happen uptown in Harlem, just a short walk from his aunt’s place. On Sunday afternoon, December 29, a copyright attorney named Bernard Stollman visited The Baby Grand Café, a club on 125th street that featured music and comedy, in order to hear Ayler, at the recommendation of a Cleveland musician he’d met. Ayler’s playing so impressed Stollman that he rushed to talk to him afterwards to say that he was starting a label and wanted Ayler to be his first artist.

Stollman signed Ayler with a $500 advance and Spiritual Unity, the album Ayler recorded for the new label, was recorded in July 1964. Though ESP-Disk was a tiny imprint with poor distribution, those aware of avant-garde jazz began to follow it closely, as Stollman documented an underground jazz scene that was growing in importance by the day. The group Ayler had assembled for Spiritual Unity, which included Sunny Murray on drums and bassist Gary Peacock, was turning quickly into a unit with an astonishing degree of empathy. Though Ayler was destined to dominate any setting he found himself in due to the sheer boisterousness of his tone and boldness of his ideas, he discovered in Murray and Peacock two expert listeners who truly understood what he was doing. Following the release of the record the group decamped to Europe, this time with momentum behind Ayler’s music.

Spiritual Unity is a classic album by any measure, but it misses something that Ayler would develop in 1965 and fully realize in 1966—how his deeply personal approach to melody and outsized expression could work in an ensemble setting. If Ayler’s bouncy march tunes were memorable when he was the sole melodic voice in a trio setting, they became overpoweringly infectious when played by a larger group.

What Ayler's New York looks like today, from left: his first NYC apartment building; the site of Take 3, where he played early gigs in the city; the site of Baby Grande Cafe, where he played a show that led to his signing; and the site of Judson Hall, where he recorded the 1965 album Spirits Rejoice.

Sensing the need for a new kind of ensemble while on tour in Europe, Albert wrote to his brother Donald in Cleveland. To that point, Donald had fiddled with alto sax and played gigs here and there in Ohio, but his playing was not particularly notable and he hadn’t developed a distinctive voice in the instrument. Albert told him to learn trumpet and move to New York when he was ready. He had two motivations. One, he and his brother were close, and Albert wanted family near him, and two, his vision for what his music could become was very specific, and required a horn in front who would play differently than anyone else on the scene at that time. Donald, who greatly admired his older brother and was excited by the idea of life as a jazz musician, could help to get him there, and he did as he was told, practicing his new horn every waking hour. Though his mother was devastated that her younger son was also leaving her and begged him not to, Donald prepared to move to New York with his brother.

By March 1965, both Ayler brothers were now living in New York. Albert had assembled a new band, one that hinted at everything his music would become during the next two years. Donald, though he had only been playing the instrument for a few months, was on trumpet. Lewis Worrell had replaced Gary Peacock on bass, and Sunny Murray was still playing drums. On March 28, for a gig at the Village Gate on Bleecker Street, just across the street and down the block from the Take 3, a cellist named Joel Freedman joined the band. It was an important evening for Albert. The new sound he was developing was coming close to reaching its final form, and the music was being recorded by Impulse!, the well-funded label whose marquee artist was John Coltrane. Coltrane was also on the bill on this night, along with astrally-focused bandleader Sun Ra, singer Betty Carter, and others. The evening was a benefit for The Black Arts Repertory Theater, founded by poet and jazz critic LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka.

In his liner notes for the live album on Impulse! culled from this evening, The New Wave in Jazz, which featured the Ayler piece “Holy Ghost,” Jones wrote that “Albert Ayler is a master of staggering dimension, now, and it disturbs me to think that it might take a long time for a lot of people to find it out.” In Jones and Coltrane, Ayler was developing important admirers. During interviews in this period, when Coltrane was asked about new players on the scene, he almost always mentioned Ayler. Coltrane loved the younger man’s music, and in the past year, they had become close. Coltrane’s approach to music was one of deep focus and relentless study, and it’s possible that he heard in Ayler’s work a kind of playfulness and intuitive musicality that was harder for him to access. And for the rest of 1965, especially, Coltrane’s sound was deeply influenced by Ayler—it’s impossible to imagine pieces like the grandly anthemic “Selflessness” and the highly melodic themes of Meditations without Ayler’s presence.

Jones’ writing also served to place Ayler’s music, and free jazz in general, in the context of the tumultuous political changes, particularly those pertaining to civil rights. From its structure to its relationship to transition, free jazz was a natural soundtrack to the broader quest for freedom and equality, and Ayler’s music in particular, which was theoretically complex but also deeply grounded in the black music tradition, had a particularly intense relationship to the moment. Ayler himself described what he was doing as the blues, but a new blues, one that fit with what was going on in the world at this time. He was making music to praise God. He thought of it less as a call to arms and more as a soundtrack to the aftermath, a vision of what the world might become when peace and equality ruled the earth.

More modern-day photos of Ayler's New York, from left: the site of The Village Gate; the site of one of his favorite venues, Slug's Saloon; the building where John Coltrane's funeral was held; and the area where his body was found in the East River in 1970.

With Donald on board and the regular addition of strings, Albert’s music was reaching the peak of its power. Unlike the horn players Albert worked with previously, Donald was neither a subtle accompanist or breakout soloist on his own. His role now was something akin to a bugle player in a military band, bleating out the themes and helping to guide the band from one section to the next. When the themes would break down and people would start soloing, Donald was prone to a series of loud trills that generally had little in the way of variation. But his tone was rich and fat, reminiscent of trumpet players from before the bebop era, and he specialized in loud, deeply felt statements of melody that gave the tunes shape. And with strings in the band, Albert’s music was developing a symphonic grandeur to match the busy feel of the New Orleans-style ensemble, the classical instrumentation reaching back to the music’s European roots as the horns stayed rooted in African-American tradition. Another ESP album, Spirits Rejoice, recorded at Judson Hall on 57th Street in September ’65, finds a version of this band—joined by alto saxophonist Charles Tyler, a friend from Cleveland—in full flower.

Through 1965 and ’66, Ayler’s ensemble would gig often at Slug’s Saloon, a small club in the Lower East Side that was especially receptive to the daring jazz being created at the time. Opened in 1964, Slug’s was developing a reputation not unlike that of Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem two decades earlier—a place for the most adventurous musicians to gather and play for each other (in 1966 and ’67, Sun Ra had a regular residency at Slug’s). As heard on the double album At Slug’s Saloon, recorded in May ’66, Ayler’s shows had grown into long medleys where one song segued into the next, and the wild energy of his earlier solos were being channeled into unbearably intense statements of melody. The music was not “free” in the strict sense of the word, but it was open and welcoming and utterly unique, with a deep feeling of joy permeating the whole.

But if Ayler’s music was reaching new artistic heights, gigs at tiny clubs like Slug’s weren’t paying the bills. Ayler’s peak years as an artist in New York were also his most financially impoverished; he was releasing records on small labels like ESP and Debut and playing small rooms, and his band had up to a half-dozen members to pay. He was often desperate, to the point where he couldn’t afford to buy food, and to get by he frequently borrowed money, most often from his father or from John Coltrane. His mentor then did him one better. In the fall of 1966, at Coltrane’s urging, Impulse! offered Ayler a record contract; a gig recorded live at the Village Vanguard in December, with Coltrane in attendance, would form the basis for his first album on the label, Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village.

Trane was able to get Ayler signed to his label, and he was there in the room at the moment when the music from his first album for the imprint was created, but he wouldn’t live to see its release. In July of 1967, Coltrane succumbed to liver cancer at age 40, and one of this last requests was that his funeral would feature performances by Ayler, along with Ornette Coleman. The service, held at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue, featured a performance by Ayler’s band—Albert and Donald, along with Richard Davis on bass and Milford Graves on drums—playing the balcony to open the event, and several minutes of the hair-raising performance survives on tape. Ayler played a medley of three of his best known themes—“Love Cry,” “Truth is Marching In,” and Donald’s composition “Our Prayer”—with an intensity and depth of feeling that almost defies belief; at the end of the segment, Ayler begins to solo on his horn and then he removes the saxophone from his mouth, screaming wildly and wordlessly in the church.

Following Coltrane’s death, Ayler’s life became a series of extremes. For a time, the Impulse! advance afforded him a certain degree of financial stability, but Ayler no longer had the great saxophonist in his corner. And Ayler’s music was on the verge of dramatic transformation, shifting to a more commercial rock and R&B sound. The reasons for this shift have never been clear. Some accounts have Impulse! executives encouraging Ayler to try his hand at more commercial genres in order to bring his music into the broader youth culture. His new girlfriend, Mary Parks, known professionally as Mary Maria, was also having a profound impact, encouraging his mystical pursuits and collaborating with him on new songs that included her lyrics. And Albert’s brother Donald, his increasingly erratic behavior fueled by heavy drinking, was inching toward what would later be described as a nervous breakdown, and was gone from the band by early 1968. That year saw the release of the album New Grass, followed by Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe. Though each has moments of adventurous experimentation remained (see the blistering bagpipe solo on “Masonic Inborn”), the albums were rife with now-dated flower-child lyrics by Parks and some shaky lead vocals form Albert. New Grass even opens with what amounts to an apology, a spoken-word section from Albert which he acknowledges that this music is different from what he’s played before, with a hope that listeners will give it a chance. Baraka’s magazine The Cricket responded with harsh reviews.

As the decade wound down, Albert was suffering from a tremendous amount of guilt about his brother’s unstable condition. His mother had not wanted Donald to move to New York, and now that he was unable to care for himself, she insisted that Albert step up. Albert and Mary wanted Donald to return to Cleveland, to be looked after at home. The rift in the family was causing an increasing amount of strain. For his part, Albert was trying for a quieter life. He moved out of Manhattan and into an apartment with Mary in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Sometimes the couple would play in the open air together in Prospect Park, he on tenor and Mary on soprano saxophone, which he was teaching her. Interviewed in Europe in 1970, Albert was asked about his place in the New York scene of the time. “It’s not for me,” he said. “I stay off to myself.”

The last months of Ayler’s life remain a mystery. The European shows were well received, and while the form of his music lacked the daring and intensity of several years earlier, recordings of two gigs find Ayler playing as well as ever. At some point during the year, Impulse! dropped him from the label. Despite his overtures to the mainstream, Ayler’s records sold badly. Some people describe Ayler behaving strangely later that year, including a report of him wearing a fur coat and gloves in the summer heat, his face covered in Vaseline. Others who saw him during these months noted nothing unusual. Mary Parks said that their precarious financial situation, coupled with concerns about Donald and the declining health of his mother, had pushed Albert into a dark place. Following an argument, he left their apartment and disappeared. She notified the police. Three weeks later, his body was found floating in the East River next to the Congress Street pier in Brooklyn, and the coroner said he’d drowned. Suicide seemed likely, but the circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

If Cleveland was Ayler’s roots and Europe was where he first saw a beautiful vision of what his music could be, New York is where all the threads of his music came together as one. In 1965, tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, another Coltrane protégé (and a great admirer of Albert), called his new album Fire Music. Four years after Coleman’s Free Jazz, the title caught the feeling of the New York present, when the crackling energy of the music and the pulsing vibrations city met the righteous political fury of the moment. Ayler’s music captured the light and heat of this particular epoch perfectly, but the intensity proved to be too much. For him, life as a musician in New York was like pushing a boulder uphill. “I’m playing about the beauty that’s going to come after the tension and anxieties,” Albert said about his music in the liner notes to Live in Greenwich Village. He never got there, never got to see what the view of the sky looked like from the top.